A Tale of Two Directors

Francis Ford Coppola's final gamit, remembering Miss Arzner, and the original It Girl...

Hi friends!

This week I’m going all-in on the movies, inspired by the upcoming premiere of Francis Ford Coppola’s self-funded epic Megalopolis, and following a daisy-chain of mentorship that stretches back to silent era with legendary lesbian filmmaker Dorothy Arzner, across the Pacific to Akira Kurosawa, and into the present with Sofia Coppola and our rising generation of filmmakers.

A special thanks to Samuel; our conversations about directing, teaching, Megalopolis & the undeniable star-power of Lucille Ball were a huge influence on my writing this week!

Francis Ford Coppola’s Final Gambit

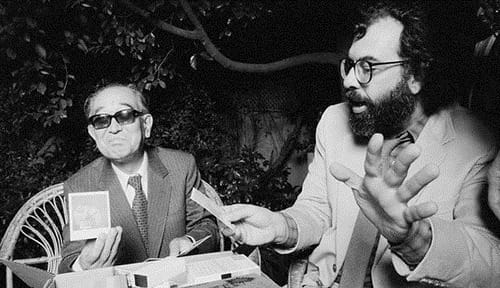

Francis Ford Coppola and Akira Kurosawa playing with polaroids in 1980.

When an artist reaches the critical and commercial success of, say, a Taylor Swift, it can become incredibly easy to coast on past glories; to risk less, repeat oneself, and protect those incredible successes (not to mention the revenue that they generate). So I’d like to raise a glass of Suntory to the irrepressible, foolhardy bravery of 85-year-old Francis Ford Coppola.

In the 1970s, Coppola directed a string of stone-cold masterpieces. The Godfather. The Conversation. The Godfather Part II. Apocalypse Now. That’s more than most artists manage in a lifetime. But unlike so many of his New Hollywood contemporaries (I’m looking at you, George Lucas), Francis has spent the decades since his early triumphs taking creative risks, often to the detriment of his career, reputation and credit rating. And his greatest gamble of all is set to play out on the world stage this week.

Francis’ struggles began in earnest with the disastrous Apocalypse Now shoot, unflinchingly chronicled in his wife Eleanor Coppola’s superb documentary Hearts of Darkness. You’ve probably heard the stories: a typhoon destroyed the sets, the helicopters were requisitioned by the Phillipines military, Martin Sheen had a heart attack, Marlon Brando turned up out of shape and eager to rewrite the whole movie, and mounds of cocaine exacerbated the director’s (already sizeable) megalomania. But in spite of the setbacks and ballooning costs, the film was a smash.

Next time he wasn’t so lucky. In the decade that followed, Francis poured money into ambitious epics that flopped (One from the Heart, The Cotton Club), and his production company American Zoetrope, optimistically founded to empower auteurs to create free of interference, was consumed by spiralling debts. His influence waning, in the 90s Francis resorted to easily-greenlit franchise plays (The Godfather Part III) and director-for-hire work from the major studios (The Rainmaker, Jack). He even started a side-hustle, opening a family-run winery in the Napa Valley which became a surprise success in the 2000s — and rescued Francis from his third bankruptcy. In recent years he’s doubled down on esoteric experimental films (Tetro, Twixt), entirely self-funded and largely unwatched by the public. These days the most prolific Coppola is of course his daughter Sofia, the finest of nepo-babies and a brilliant director in her own right whose oeuvre, including the likes of The Virgin Suicides, Marie Antoinette and Priscilla, arguably rivals her father’s.

The final act of Francis Ford Coppola’s story is still being written. Tomorrow, the Cannes Film Festival will premiere his latest film, the science-fiction epic Megalopolis. Inspired by the Catiline Conspiracy, an attempted coup in the Roman Republic in 63 BCE, re-imagined for a near-future United States, the film features an eclectic cast including Adam Driver, Aubrey Plaza, Shia LaBeouf and Laurence Fishburne. Not only has Francis poured “everything I ever read or learned about” into the film; he’s also poured in all of his wealth. After decades of rejection from the major studios, Francis took matters into his own hands to bring his dream project to life. He sold his winery and used the proceeds to fund the $120 million USD budget. It has all the hallmarks of one final throw by an old master in his twilight years.

But in an all-too-familiar turn of events, instead of breathless anticipation, so much of the chatter around the film has forecast failure, and centred on Francis’ hubris. Over the past month, Coppola has been screening his film to industry figures and studios, fishing for distributors willing to market and release this experimental epic. Word of mouth is that the film is “batsh*t crazy”, “downright confounding”, “fit for a museum” and, the most dangerous word of all, “uncommercial”. Although he’s found interest in France, Germany, Italy, the UK and Spain, no studio or distributor in the United States (or Australia for that matter) has taken the bait. Even worse, many studios seem to be actively working to undermine Coppola and his film via anonymous attacks in the industry trade papers.

It’s a terrible indictment of the state of the industry when the crowning work by a major artist like Francis Ford Coppola struggles to find an American distributor. Of course, there’s no telling yet whether we’re looking at an Apocalypse Now or a Youth without Youth, but surely the director of The Godfather has mustered enough credit for a distributor to bring his latest (and quite likely final) work, brimming with movie stars and big ideas, to general audiences to make their own decision?

But perhaps this risk-averse behaviour shouldn’t surprise us in 2024. For every Martin Scorsese — who has an uncanny knack for conning the Oscar-hungry streamers into funding his passion projects — there’s a David Lynch, who has seen his last two projects scuttled at the last minute by Netflix (an animated feature and a new TV series starring Laura Dern and Naomi Watts, how dare they). Whilst some indie filmmakers thrive outside the confines of the studio system — creating stunning work with only micro-budgets and local screen grants — many of our great artists benefit from a broader canvas, and they’re the ones who’ve suffered most from corporate slates dominated by sequels, superheroes and video game adaptations. A24 can’t nurture every budding auteur out there.

It’s not a new dilemma of course; history is littered with stories of artists who find themselves cut adrift by money men and spurned by the public in their old age. The mighty Rembrandt sunk from glory to destitution due to poor financial management and an out-of-vogue late experimental style. Herman Melville prematurely retired from novel-writing, and found work as a Customs Inspector to subsidise his poetry. Orson Welles spent his final years voicing Transformers and shilling cheap wine on TV to scrounge up the money to finish his avant-garde films (and unlike Francis, poor Orson didn’t own a stake in the winery). Even the peerless Akira Kurosawa couldn’t find any backing from the Japanese studios in the 1970s. But when there was a funding shortfall on the 70-year-old Kurosawa’s comeback epic Kagemusha, who came to his rescue?

Francis Ford Coppola, that’s who. Francis appeared in a series of Suntory Whiskey commercials in Japan to help raise money to complete the film (an experience that informed Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation years later), and partnered with George Lucas to bring American distributors on board to complete and release Kagemusha.

For all their flaws (and believe me, they’re well documented — I don’t think “old-school” Francis has ever been described as a pleasure to work with), Coppola and his New Hollywood peers deserve our respect for all the ways they’ve consistently championed their fellow filmmakers and the art form as a whole. Martin Scorsese has spent decades elevating international voices, bankrolling the restorations of global masterpieces through the World Cinema Project and African Film Heritage Project, and executive producing work by young directors including the Safdie Brothers, Alice Rohrwacher and Josephine Decker. Even George Lucas funnelled most of those dirty Star Wars billions into education initiatives and a new Museum of Narrative Art.

The old guard won’t be around for much longer. Who’s going to take their place? We can hardly rely on the international conglomerates and Silicon Valley monopolists that now dominate Hollywood to champion audacious art — we never could. And the system they perpetuate is creating fewer marquee filmmakers with genuine power, widening the gulf between a few winners and the growing underclass of artists struggling to survive project to project (a phenomenon that’s certainly not unique to film & television!). Short of a wholesale revolution, I think it’s high time for today’s mega-rich directors and producers — the likes of Christopher Nolan, James Cameron, Peter Jackson & Robert Downey Jr. — to more actively support the work of their forebears, peers and the generations to come. Tarantino and Del Toro can’t do it on their own!

Yes, Francis Ford Coppola is hardly the poster-boy for “struggling artist” (if Megalopolis flops he’ll be fine — he's still got a mansion in Napa to retreat to, or can mooch off Sofia) but I believe everyone — audiences, artists and critics — benefits from a culture that encourages audacious movie-making. Those with means should be chipping in and leveraging their prestige and power, just like Francis did all those years ago for Akira Kurosawa. And I hope the rest of us can stop sharpening our knives, and instead champion Francis’ final gambit. Even if it fails. Especially if it fails.

Tomorrow, Megalopolis premieres at Cannes. Perhaps it will be a disaster; one last act of hubris from an aging megalomaniac. But in an era where it’s become rarer and rarer to see any risks at all in the realm of big-budget filmmaking, any attempt at original, personal and boundary-pushing work should be savoured and cherished. That’s how we encourage today’s filmmakers, and the generations that follow us, to take the risks that the art form needs if it’s going to thrive for another century. For over sixty years Francis Ford Coppola has invested all his passion, creativity and capital into cinema, and enriched it (and us!) in the process. The least we can do to offer the same love and support right back.

Thank You, Miss Arzner

Dorothy Arzner and her star Clara Bow on the set of The Wild Party (1929)

It’s a precious gift for a budding artist be be taught by a master of the form, and clearly Francis Ford Coppola was born under a lucky star. His teacher and mentor in the UCLA directing course in the early 1960s was Dorothy Arzner, a retired director from the Hollywood’s bygone golden age. Francis recently recalled a moment when, early in his degree and already out of money, he was contemplating dropping out:

She stopped and she handed me a box of crackers that she always had with her for her hungry students and she said to me, ‘You’ll make it, I know. I’ve been around and I know.’ Then she disappeared into the shadows like the ending of one of her movies… I can never thank you enough, Miss Arzner, for the many things you taught me, all of which helped me through the next fifty years of my career and for your prediction that gave me the confidence to go on and become a film director.

Although her films were largely forgotten in Francis’ student days, today “Miss Arzner” (as her star pupil still calls her) is lauded as a trailblazer and feminist icon: the only woman directing films for major Hollywood studios in the 1930s and early 1940s, the first woman in the Director’s Guild, and a lesbian in an era of fervent conservatism who lived openly with her partner, dance choreographer Marion Morgan, for forty years.

Despite frequently being lauded as a Hollywood “pioneer”, I think it may be more accurate to label her a survivor. After all, there were dozens of other successful female film directors, writers and editors in the silent era (including Lois Weber, Frances Marion and Dorothy Davenport), but most were muscled out over the course of the 1920s as the business boomed and more capital poured into the nascent industry. It’s worth acknowledging that Arzner was buoyed by private family wealth, which gave her more freedom to pick and choose projects (and, eventually, call it quits) than her peers — not unlike patrician Katharine Hepburn, whose dashing on-screen tomboy persona Arzner helped to shape in their early film together, Christopher Strong.

Arzner alone survived the transition to sound, bolstered by a string of hits with Clara Bow and Fredric March, including Paramount’s first talkie The Wild Party. She’s even credited with inventing the boom mic, allowing the sound recordists to follow the fast-moving and improv-loving Clara around the set. In fact, Clara Bow’s struggle with fixed mics was the inspiration for the virtuoso sequence in Damien Chazelle’s Babylon depicting Margot Robbie’s traumatic first day on a closed sound set. Margot’s free-wheeling character is clearly modelled on Bow, and her on-screen director’s sartorial style is suspiciously reminiscent of Arzner…

After fifteen years as one of Paramount’s top directors, Arzner retired from features in 1943 to teach and work in commercials (not an uncommon career trajectory even today); the mantle of “the only working female director in Hollywood” was taken up by Ida Lupino a few years later, under the “there can only be one” Highlander rules that persisted into the 70s. In the decades that followed, Arzner was most influential as an educator. Her first teaching role was with the US Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) during WW2, where she mentored enlisted service-women and taught them to make training films. After the war, she developed and led some of the world’s first college-level film courses, first at Pasadena Playhouse and then finally at UCLA, where she taught Francis. Arzner’s method favoured on-set experience over academic theory, and popularised shooting 16mm short films; her students would make eight or nine shorts every semester (!).

However there’s a danger that, in reducing Dorothy Arzner’s career to its “firsts”, we praise her for trailblazing without actually engaging with her art. Her triumphs include the pre-code dramedy Merrily We Go to Hell (1932), about a dysfunctional couple testing out an open marriage, and Craig’s Wife (1936), starring Rosalind Russell as a materialistic woman who weds for wealth and power. Oh yes, you certainly get the sense that Arzner had her doubts about heteronormative marriage. My personal favourite of her films is Dance, Girl, Dance (1940), a sharp-tongued romp that I think is the best and bravest of that era’s beloved backstage musical-comedy sub-genre.

The radiant Lucille Ball in Dance, Girl, Dance (1940)

At first glance Dance, Girl, Dance looks achingly familiar: it’s a tried and true tale of dancers dreaming of making it big in the Big Apple. But Arzner, working with a script by Tess Slesinger & Frank Davis, clearly has more on her mind. From its very first scene, where the girls appeal to a policeman breaking up their show — “we’re just trying to earn our living, same as your are” — the film has a preoccupation with the nexus between women, selfhood, art and money that feels starkly contemporary. The dancers’ dilemma will feel familiar to any jobbing artist: the girls can barely make the rent, surviving on short-term gigs in sleazy dive bars and making short-term compromises in the hopes that something better will eventually come along.

The film’s greatest triumph is to set up a conventional Good Girl / Bad Girl dichotomy between its leads — Judy (Maureen O’Hara), the purist who dreams of becoming a great ballerina, and Bubbles (Lucille Ball), the party girl who is willing to trade on her sex appeal to make bank — only to subtly undermine it. A lesser film would reduce the flighty sexpot Bubbles to a villain, but Arzner is careful to fully illustrate Bubbles’ belief system: her goals are comfort and security, and she’ll use all her god-given gifts to achieve them. In doing so, Bubbles also lifts up her fellow dancers, trying to find them work and secretly paying their rent even as they treat her with a whiff of moral condescension. It certainly doesn’t hurt that Lucille Ball just screams “STAR” — it’s a real shock that it took another decade for her to go supernova with I Love Lucy.

Meanwhile our “goodie two shoes” Judy spends most of the film chasing a transparently shitty dude and sticking her nose up at the opportunities Bubbles gives her. But it’s Judy’s simmering discomfort with the leering male gaze — the trade-off she must accept in order to occupy any stage, from an underground club to a Broadway theatre — gives the film its greatest immediacy. In one bracing early scene, the troupe perform the hula to a promoter in hopes of convincing him to hire them. The man watches from a chair in the corner the room, staring at their bodies as Arzner cuts closer and closer to his disinterested, unblinking face, his mouth closed around a long, stiff cigar. We watch him watch… but through his POV we’re also watching and judging the girls. Decades before Laura Mulvey, Arzner is teasing out the complexities of the camera’s gaze, and our complicity as audience members. That tension finally erupts in the film’s most audacious scene, where Judy stops mid-performance to rail against her own audience, breaking the fourth wall of the stage, and perhaps the screen too.

Go on, laugh, get your money's worth. No-one's going to hurt you. I know you want me to tear my clothes off so you can look your fifty cents' worth. Fifty cents for the privilege of staring at a girl the way your wives won't let you.

Dance, Girl, Dance still has the power to genuinely surprise and challenge us, but it’s not all feminist critique; Arzner is making a comedy after all, and the film is reliably funny, madcap and unpredictable. It’s admittedly also a bit rough around the edges, haphazardly darting from one set-piece to another, and you can just feel the script pushing right up against the restrictions of the conservative Production Code — without ever quite crossing the line.

But that’s Dorothy Arzner in a nutshell. She was never an outsider artist, like her student Francis Ford Coppola proved to be. Her gift was for making films within the classic Hollywood studio mould, whilst nonetheless infusing them with flashes of daring, challenges to conventional values, and a deep empathy.

We, like Francis, were lucky to have her.

Odds & Ends

A tail of two thefts — Rebecca Mead has written an excellent piece for the New Yorker about the twin crises that have engulfed the venerable British Museum (it’s evil but I also love it, my eternal struggle): the recent theft of valuable artefacts by the Museum’s own employees (oops), and the Museum’s ongoing refusal to return the Parthenon Marbles to Greece. Taken together, they’re completely eroding the Museum’s reputation and moral authority.

For further reading on the dire state of modern Hollywood, check out Daniel Bessner’s well-researched and sobering piece. From Showrunner Alena Smith: “It’s like a whole world of intellectuals and artists got a multibillion-dollar grant from the tech world, but we mistook that, and were frankly actively gaslit into thinking that that was because they cared about art.” Ouch.

And for anyone curious about original “It” Girl, silent superstar Clara Bow (whether that’s thanks to her role in Dorothy Arzner’s career, or, more likely, a recent track by Taylor Swift), my favourite film history youtuber Be Kind Rewind just released a comprehensive piece about Bow’s life and career. “You look like Clara Bow / In this light, remarkable.”

And that’s it for this week, thanks for reading!

Reply